For organic chemist Henri Sund, coaching an amateur football team helped him discover a passion for leadership. Through mentorship and the Danaher Business System (DBS), Henri nurtured his talent, and now leads his own team of scientists as a senior manager in assay development. Below, Henri discusses his journey from research assistant to team leader, how DBS empowered him to take on a mentorship role and how he’s guiding his team through the transition to a hybrid work model post COVID-19.

What do you do at Radiometer?

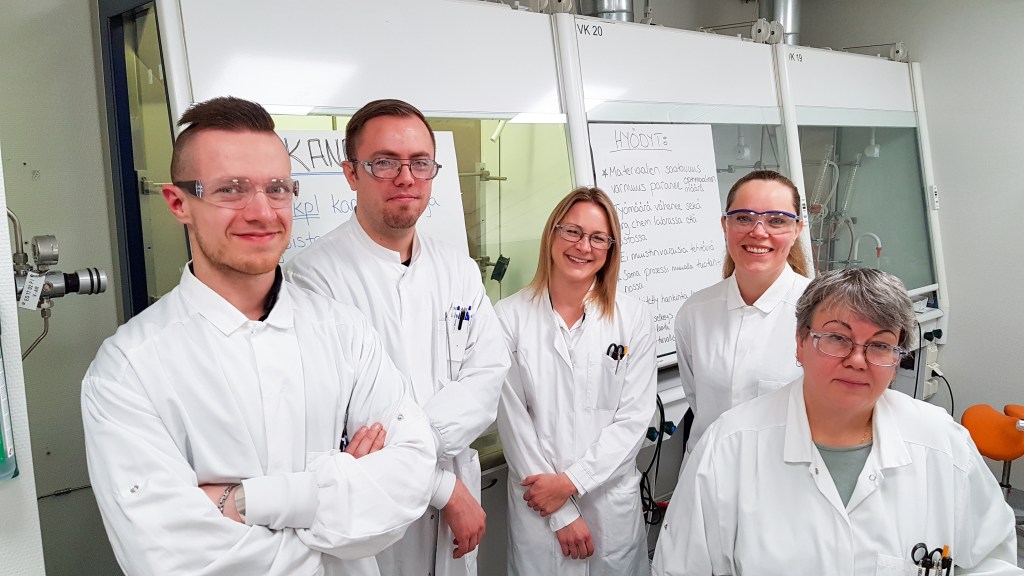

My two main responsibilities are to lead my team and to secure continuous development of tools and workflows for the R&D department here at our site in Turku, Finland. I manage a great team of nine chemists and scientists who develop dry chemistry-based test kits for our immunoassay product line. More specifically, it’s the test cartridges that hospitals and other health care providers use in a Radiometer immunoassay device—similar to a coffee pod or an ink cartridge for your printer. My team members work on new product development so they really make a difference in providing caregivers with point-of-care (POC) solutions to make fast and accurate diagnoses.

We have project managers who are responsible for the progress of each project; my job is more focused on the team itself. I make sure they have the tools and support they need to do their jobs effectively; I keep an eye on their workloads and I mentor them on how to build and grow their careers further.

Our big focus right now is automation and digitization. We’re looking for opportunities to streamline processes and eliminate “muda”—a Japanese term meaning “wasteful” that we often use within DBS. We want to remove unnecessary manual steps to make better use of people’s time. We’re also upgrading equipment to make it compatible with the current systems for analyzing and utilizing data. We already gather tons of information, but we’re still laying the groundwork to make that more organized and easier to use.

What led you to this role?

I basically started my professional career here at Radiometer. I studied organic chemistry at the University of Turku, and while working as a temporary research assistant for the Department of Biotechnology we were collaborating with Radiometer on some projects. It was motivating for me as a young chemist to get to contribute to something new and to have support and mentoring from the team. They invited me to do my thesis work here, and after I finished that I officially joined the team in 2010.

Early on, my goals were very research-oriented, in part because I admired my mentors so much. I was working with these widely known experts in the field, and I wanted to be just like them! But over the years, I started getting more interested in management. At one point, I started coaching amateur football as a hobby, which taught me a lot about what to do and what not to do, working with people from different backgrounds and keeping them motivated. Then in 2017, I became laboratory supervisor for our organic chemistry lab, which is a cross-functional group that includes both Operations and R&D.

During those earlier years, I got to better understand the DBS tools, like Problem-Solving Process and Situational Leadership, and that led me to a sort of an “aha!” moment. I realized there were a lot of shared values with what I’d learned as a coach. So I started to think the manager path might be a good fit. My own managers suggested different trainings to help me prepare for a leadership role and see how I would like it, and then last year this opportunity came up.

Even though I’d been preparing, I was hesitant at first. I’ve worked in assay development my whole career, but as an organic chemist in a research team. This role also meant managing people in biochemistry, biotechnical engineering and other fields—which aren’t my areas of expertise. I wondered, “Can I really pull that off?” I wanted to make sure I could create the trust I needed to fully support people. I decided to go for it, and I’m very glad I did.

Tell us more about that. What’s the transition been like?

It’s been a lot of me learning—about my team members, the details of their work, and the kinds of challenges they face. We did a lot of one-on-ones, especially in the first year, to help us get to know each other. Of course, every relationship is different. There are some associates I’ve worked with for years—so we had to figure out the dynamics with me leading the team—while others I was meeting for the first time.

Because I was focused specifically on organic chemistry until last year, I’m not always the person to give my associates the answers or tell them what to do. I ask a lot of questions; it’s more about thinking through together how they might solve a problem. We’ll find someone in their area they could talk to, or I’ll give them insights from my experience that might apply. Whenever I can help by sharing something I learned in a similar situation, not just specific tasks, but navigating challenges and ups and downs, those are the most rewarding moments for me.

How have you and your team navigated the challenge of remote work since the emergence of COVID-19?

Like most companies, we’ve been through a lot of change in the past couple of years because of the COVID-19 pandemic—but of course, that doesn’t affect everyone the same way. If you’re doing research in a lab or working on our Production team, you probably don’t have the option to work from home often. With this new role, I’ve been able to work remotely, although I’ve always been mostly on-site.

The last year was a bit hectic just because I was learning so much that was new, but I do have the freedom to decide where and when I do a lot of my work. I still regularly work on-site to make sure I’m on top of what’s going on in our facilities and to help me stay connected with my team.

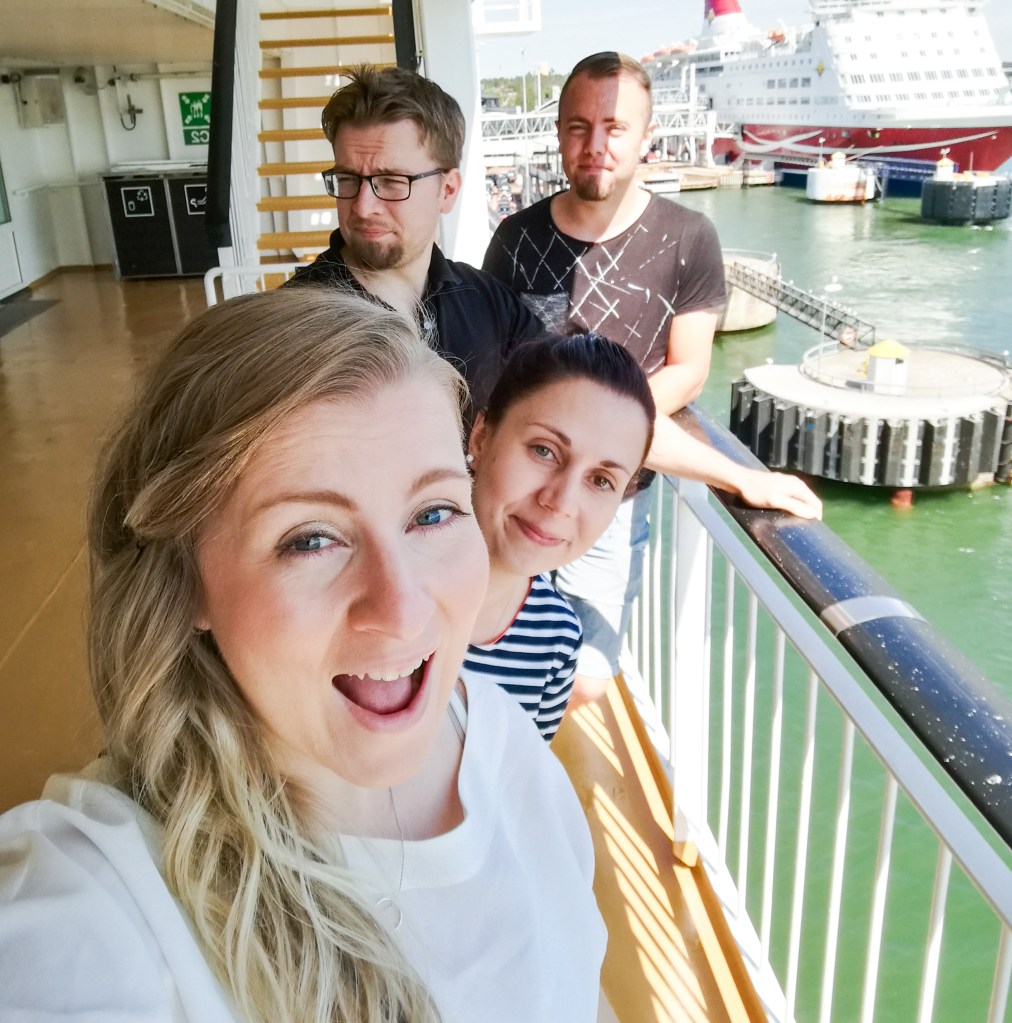

We’ve now officially moved to a hybrid model, meaning everyone is on-site at least two days per week. We’ve had workshops about different models for the future of work, and it’s been really interesting to hear how associates feel about their workdays and what the downsides and upsides are of working in person versus at home.

We’re thinking a lot about how we can make each arrangement work—scheduling meetings differently, for example, or aligning the days certain groups are at the office so they can collaborate more easily. It’s a very personal thing—how you respond to different situations, what you need to be productive. But at least for me and my reports, we’ve found a lot of value in flexibility, being able to fit work and family into the day. I’m very much looking forward to seeing what kind of possibilities these new models will bring.

As a manager, how do you help your team members grow their careers?

I’ve been very fortunate in my career to have great managers and other mentors who got to know me quite well, and when they sensed I needed support or was ready for a new challenge, made suggestions. I’m so grateful for that, and I try to do the same for my team, in part by just sharing my own story and learnings. If someone is wondering about career progression, it’s quite natural for me to talk about how I started and that there was a long period of time where I thought I’d stay in the lab, or was stuck there, but then a different path opened and I started work systematically to achieve it. It raises a question for them, “Okay, what could my version of that story look like?”

One thing I avoid is telling them directly what I think they should do, because it’s easy to influence someone and I know firsthand how important it is for people to feel free to change their mind.

I know my team members might find it frustrating at times that I don’t just tell them what they should do. But it’s important to really listen—to pick up on clues: what kind of work do people do, what motivates them, what makes them feel alive. Then I suggest DBS tools or other areas of potential interest, but what’s exciting is letting it all play out.

You don’t have to know from the start where you want to go. Everything someone experiences and learns will play a role in helping them find their path, and it’s my job to support them on that journey.

Leave a Reply